[TRIBUNE] OPPORTUNITIES OF LIVING IN AN URBAN AND LOW-TECH ENVIRONMENT

Date of publication : August 29th 2022

Author : Andréane Valot

English translation : Heather Foster

The Low-tech Lab regularly gives the floor to experts. Today, Andréane Valot, designer and graduate of ENSCI - Les Ateliers in 2021, shares her assessment of 8 months of experimentation with a low-tech approach to life in an urban environment, in this case applied to her Parisian studio. As an individual, she puts her energy and skills at the service of public interest and the ecological transition, halfway between social innovation and low tech.

LOW TECH EXPERIMENTATION IN APPARTMENTS #

1. INTRODUCTION #

At a time when French Government policy on conservancy continues to lack ambition, the low-tech approach is becoming more widespread among citizens and organisations concerned about reducing their impact and consumption. For individuals, the most straightforward and affordable opportunities are found in the home, involving, more precisely, the consumption of energy, water, and building materials. But whereas it is rather easy to recover the tools and techniques of one’s daily life when one enjoys autonomy in transforming one’s habitat, in other words, when one is a landowner and/or lives in a space that is sufficiently independent to make arbitrary transformations, collective urban housing assumes a completely different mode of dwelling, which is often very standardised, constrained and dense, making it more difficult to adapt.

This observation became clear to me when I left my family house to move closer to my place of study. Like 75% of the inhabitants of Paris, I found myself living in this very particular and yet so common form of housing, that is, renting a flat in a condominium. Faced with the immense issue of adapting to climatic and social upheavals, condominium housing is both the subject and the reflection of several major problems, both on a local and global scale.

2. THE SPECIFIC CASE OF JOINT OWNERSHIP HOUSING #

Firstly, this housing context is particularly interesting because it is built on several paradoxical foundations which make it a reflection, on a reduced scale, of our contemporary organisations and the systemic blockages which result from them. Thus, one could compare a condominium to a micro-society. It is, on the one hand, a complex place, which articulates private spaces and common elements. But it is also a human community, random, mixed and diversified, where tenants and owners, users and managers are mixed. Finally, it is an organisation, governed by decentralised and hierarchical modes of governance, in the vast majority of cases.

However, the condominium, as a collective dwelling distributed within the same complex of dwellings, is currently the most suitable model for the density of the city as we know it, and perhaps even the most “ecological” in this particular context, since it is the most optimised and rationalised from the point of view of the consumption inherent in the dwellings. But paradoxically, the management methods used today, in most cases, make it an extremely complex model to change, precisely at a time when the climate emergency and social justice are urging us to change our behaviour as a society but also as individuals.

In its classic management model, co-ownership brings together all the co-owners in an assembly of decision-makers, which is itself governed by a trade union council made up of a few elected co-owners, all of which is supported by a trustee, a third-party organisation, to which the co-owners generally delegate the hiring of contractors, caretakers, maintenance workers and other tradesmen likely to intervene within the building. More concretely, this sharing of ownership necessarily implies decision-making by agreement to undertake any maintenance or modification action on the building and the common infrastructures, and therefore a certain financial investment, shared in proportion to the surface area owned by each owner.

However, for 42% of owners in France, owning a flat is a profitable financial investment rather than a means of housing. As a result, in the extreme but increasingly common case of a building managed by a large majority, if not all, of co-owners who are landlords, and therefore inhabited mainly or even exclusively by tenants, the question of the uses and needs of the inhabitants is relegated to second place, behind the financial interests of those who own. In a condominium, any modification of the layout, any maintenance action, any management organisation depends on the condominium syndicate, in other words on the condominium owners’ meeting. The tenants, on the other hand, have no say in the management of the property. Legally, they do not even have the right to initiate any modification in their dwelling without the agreement of the owners. It is therefore, in particular, this dichotomy between management and use, between what is owned and what is lived in, which makes the model of co ownership potentially locked.

Let us now take the example of a condominium where the owners, almost all of whom are landlords, have taken the collective decision to commit time, money and material to making their building more energy-efficient in terms of heating by installing thermal solar panels to heat the water in the circuits. In this case, since the decision-makers and users have not agreed on the benefits of such an installation, tenants may, for example, be inclined to turn up the thermostat on their radiators rather than dress warmly enough to be comfortable in their homes. Like the controversy surrounding electric SUVs, thinking of a technical innovation as a way of limiting consumption without accompanying the associated behavioural changes will never do anything other than make use of it less easy and thus perpetuate, if not increase, the excesses of the myth of unlimited consumption.

On the other hand, in the case of a community of inhabitants, the majority of whom are tenants, who wish to limit their energy consumption linked to heating, this will necessarily remain constrained by the collective infrastructures, and therefore by the goodwill of all the owners to adapt them. However, in the most common form of management of a condominium, the tenants, their opinions and their experiences are not solicited at all during the decision-making process. Renovation or redevelopment projects in this type of condominium are generally based on technical and financial diagnoses which do not take into account the real uses.

What about low-tech for urban housing?

Let us now observe a second paradox, this time more macroscopic. In addition to the reasons mentioned above, urban housing is also complex to develop in terms of its uses and infrastructures because of the standards imposed by urban areas and/or the rules of use included in the co-ownership regulations, which are not conducive to a quest for energy efficiency. Moreover, it is currently not very feasible, or even desirable from a health point of view due to the demographic concentration of the city, to include in an urban setting as dense as Paris a certain number of well-known low-tech solutions that have proved their worth in rural or, at least, sparsely populated and more autonomous contexts.

To cite just a few of the most consensual examples in the low-tech community, a collective composting system integrated into the building would be too inefficient to transform the quantities of organic matter (food waste and/or manure) generated by all inhabitants above a certain number. Rainwater is currently banned for domestic use in several large cities, including Paris, making tank systems illegal other than for watering plants. Condominium bylaws often prohibit the installation of a pantry on the windowsill for fear of rodents colonising the premises. The installation of systems using solar energy to heat or produce electricity is also often prohibited, either because of the poor exposure of the building or its enclosure among taller buildings, or because of the Local Urban Plan and/or the Architectes of Bâtiments de France, who will impose the preservation of the aesthetic harmony of a building set in a remarkable context.

Finally, since the questions of ownership and community seem to condition the user’s margin of adaptation, let us ask ourselves this very simple, yet so complex question: How can the inhabitant recover his or her habitat, when it does not belong to him or her? … or at least not completely.…

Story of a year of experimentation

The following article is the narrative and commentary of a citizen's experiment carried out at the level of the house and the building where I live. It aims to question the a priori low margin of action of the tenant in a condominium, and more generally of the citizen in society.

Nearly a year after the beginning of this personal and collective transition project, these few paragraphs constitute the assessment of what remains of it, its evolutions and the lessons that we can draw from it today.

However, before developing some of the proposals tested, it seems to me essential to stress that all the examples that will be mentioned here have been designed to adapt to the precise context of this project, this building, located in this place, anchored in this territory, with its particular history and its specific material and human parameters. If we were to repeat the process in other buildings, the answers would certainly be quite different. The account I will give here is therefore intended to illustrate a global approach, to be a support for inspiration rather than a repertoire of solutions to be reproduced without alteration.

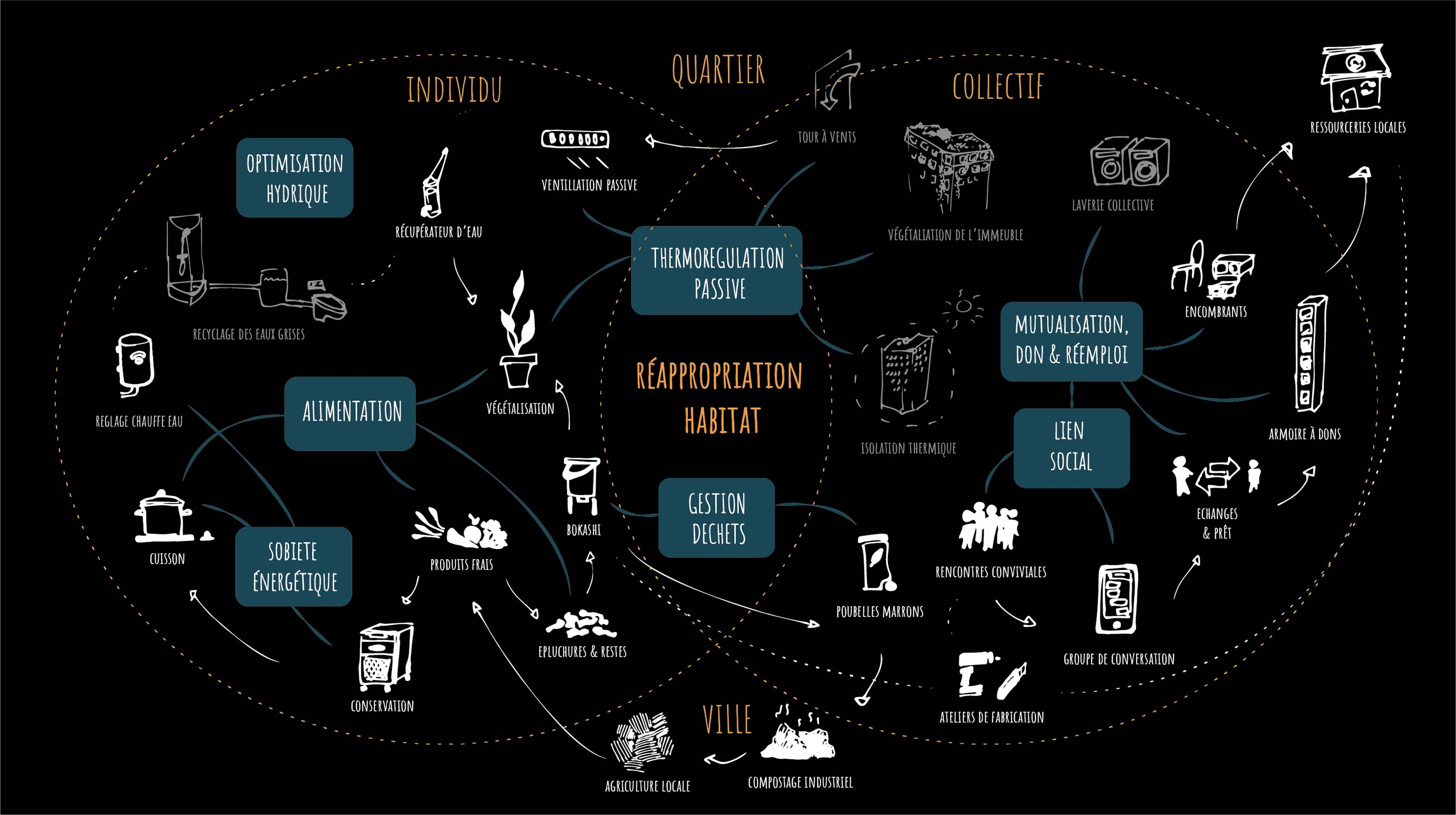

3.TO ESTABLISH DYNAMICS OF COLLECTIVE REAPPROPRIATION #

« Where the inertia of the condominium model has decoupled “use” and “manage”, “live”and “take part”, “be part” of a community, a place, a human and non-human environment, and “take care” of a pluralistic, living and material space-time, it is up to us, the inhabitants, to recover the conditions of our lifestyles in order to advance towards greater resilience and adaptability in response to the challenges of our century. In this respect, the collective dimension of condominium housing seems to me to be one of the most significant issues to be raised.

Involve users, ease collective thinking, develop common interest

Since any appropriate response depends on the context in which it is set, the first step in setting up such a project is to take a closer look at the contextual elements: the history of the place, its material nature, the networks that run through it and the uses to which it is put, the territory and environment in which it is located, its orientation in relation to the natural elements, the profile and situation of its inhabitants, their experience of the building, etc. These will enable us to provide more relevant responses to the needs raised. They will enable us to provide more relevant answers to the needs raised.

One of the first lessons learned from this experiment is the realisation that rebuilding community requires above all finding places suitable for meeting, and planning common moments to build a space for exchange and cooperation. A public park, a bar, a backyard, a temporary hallway or a host flat can thus accommodate this collective time-space that is so important to the cohesion of a group.

Questionnaires, information flyers, door-to-door surveys, consultation workshops or even a neighbours’ party and aperitif-discussions are all means that have enabled us to establish an initial contact and to define the common needs and desires of the inhabitants concerning their habitat.

Together, we have tried to act, at our level, on the problems of common interest that have emerged:

- Communicate and connect with other neighbours,

- Share/give/lend equipment,

- Better waste management,

- Greening and landscaping of common areas,

- Renovating and adapting the condominium’s spaces.

After defining these first guidelines, we founded a collective of residents ready to invest a little time and brainpower to think and act together, at our level, on intermediate solutions. While waiting to be discussed at the General Assembly with the co-owners, these solutions will allow the users of the premises to adapt their living spaces, their equipment and their daily behaviour, starting today and at little cost. Beyond these first avenues of recovery, the idea is to progressively achieve a more inclusive management of the building, by giving the voice of the residents, tenants or owner-occupiers in the minority, to the co-owners’ assembly.

Co-constructing conviviality

The first system set up to meet the needs of the residents is a messaging system (WhatsApp) that everyone can join independently and voluntarily via posters in the building’s lobby. This group is initially a virtual space for internal meetings and communication. On the other hand, it is also a network for lending, selling, exchanging, donating, giving advice and providing services between neighbours to encourage collective solidarity and a certain circularity within the building. Moreover, thanks to its capacity to facilitate the creation of links and to preserve a good understanding within the building, it makes it possible, once trust has been established between the interested parties, to orchestrate a solidarity-based sharing of bulky and/or expensive domestic equipment. Where the lack of space and means can lead to insecurity and malaise, the sharing of equipment becomes a lever for optimising the use of resources and better distributing living comfort within the collective housing. For example, sharing a fridge, a washing machine, a Wi-Fi box, a hoover or a drill are all small things that participate here, on their own scale, in combining social, economic and environmental cohesion.

As simple and common as this discussion group may seem, it was in fact a key stage in this project, since it allowed and still allows for the creation of a feeling of belonging to a community, where the context of urban co-ownership is rarely predisposed to conviviality. This is a first victory against the legendary frigidity of Parisian relations.

However, this type of platform has its limits, particularly in terms of the inclusiveness of older people or those who do not have a smartphone. It should therefore be complemented by other communication channels. Among those we have been able to experiment with so far, the door-to-door format, the corridor discussion and the newsletter also work well as a complement.

At the same time, to allow for more spontaneous and practical solidarity, we decided to install a self-managed donation cupboard in the hall of the building. Inhabitants can freely and anonymously deposit what they no longer need (small objects, clothes, books, CDs, DVDs, magazines, accessories, etc.), and find additional information on the management of their other bulky items (bulky objects, perishable products, etc.). This part of the project is more obvious here because it is linked to the history of the building and to the crystallisation of the split between inhabitants and landlords, between use and management. In the building, this type of initiative had already partially emerged, but had each time been repressed by the union council, which rejected the disorganised and disorderly character that a pile of loose objects in the hall gave to the building… It was therefore above all a symbolic action that was carried out here, both to establish a position of the residents for a convivial reappropriation of the premises, but also a compromise as a token of good understanding with the co-owners (the cupboard was adapted to be visually discreet although it is active every day: Its shapes and colours blend perfectly into the hall and the semi-opaque tiles of its door conceal the objects to be donated while subtly evoking their presence).

We are very proud that this initiative has been very well received by the residents and owners, and the cupboard is now and will be for many years to come in the hall of the building.

Beyond these first improvements to our living environment, which are very simple and effective, we are working together on larger-scale projects with the co-owners, such as the idea of setting up a self-managed collective laundry room in place of the old communal toilets, which are currently condemned, or a file or a case for a thermal renovation project for the building’s critical facades.

Community life, one year later

One year after the start of the project, there is still a good general atmosphere in the building, with frequent cocktail parties between neighbours and friendships being made, helped by a climate of trust and mutual support. Of course, not everyone has the same dynamic, but newcomers are generally pleasantly surprised to find such a warm welcome and such a comfortable (human) life in Paris. The last few months have certainly been quieter, with projects temporarily put on hold due to a lack of joint availability, but a great deal of recognition and respect for the solutions already put in place remains palpable on a daily basis.

On a personal level, the project as a whole has led to a considerable increase in my living comfort. Knowing my neighbours and maintaining good relations with them has allowed me to freely use additional spaces and equipment lent by these friends of the building. More fundamentally, they provide real psychological and technical support when needed, which gives me a great deal of peace of mind on a daily basis.

4.ADAPTING YOUR HOME - TRANSFORMING ITS USE #

In addition to orchestrating a form of conviviality within the building, sharing what can be shared and organising together to make the voice of users heard at the General Assembly, it is necessary to undertake a process of reappropriation at the individual level in parallel. In order to create a more resilient and sober society, it is no longer necessary to demonstrate the urgency of re-examining our uses, our consumption and their legitimacy in relation to the needs they meet. And if, initially, it is important to try to reduce what is not very useful, or even superfluous, we must also look for other ways of doing things, other techniques to meet the needs that we consider useful in our present context (the needs vary according to the personal context of each person).

Analyse my context, question my uses

So, let’s start by analysing the more precise context of an individual flat: mine, as a guinea pig.

My personal context is that of a typical Parisian studio apartment, 15m2, under the roof, on the 7th floor of an almost century-old building, not insulated, facing south, with only one window, and whose equipment provided for rent is, for the most part, outdated. Moreover, since it is located in the heart of a very dynamic district, it allows me to benefit from a great proximity to shops to meet my food and material needs.

In the home in general, the most energy and resource intensive needs are hygiene, food and temperature control. Let’s now look at the need for the uses that arise from these.

For example, it is essential for me to maintain good personal hygiene. But is it really necessary for me to take a shower every day (an average of 50L/shower) or can I simply wash with a glove on certain days (an average of 2L/wash) depending on the effort and temperature during my day? Since half the time of a shower is usually spent warming up rather than washing, can I turn down the thermostat on my water heater, or even turn it off, without risking my health?

On the subject of food, it is essential for me to eat every day: on the other hand, is it essential for me to keep food in the refrigerator so that it stays fresh or, because of the proximity of shops, can I buy less and more regularly my fresh products? To limit my plastic and cardboard waste, I need to cook fresh products (also because I like to cook and eat healthily), but can I optimise my cooking time and techniques, or even explore more raw recipes to limit my energy consumption?

Faced with the heat waves that are likely to become more severe and commonplace in the city in the coming years, it is essential for me to regulate the temperature of my flat in order to maintain a minimum level of comfort, but can I find efficient passive solutions rather than buying energy-consuming equipment that is harmful from a systemic point of view (air conditioners / electric fans)?

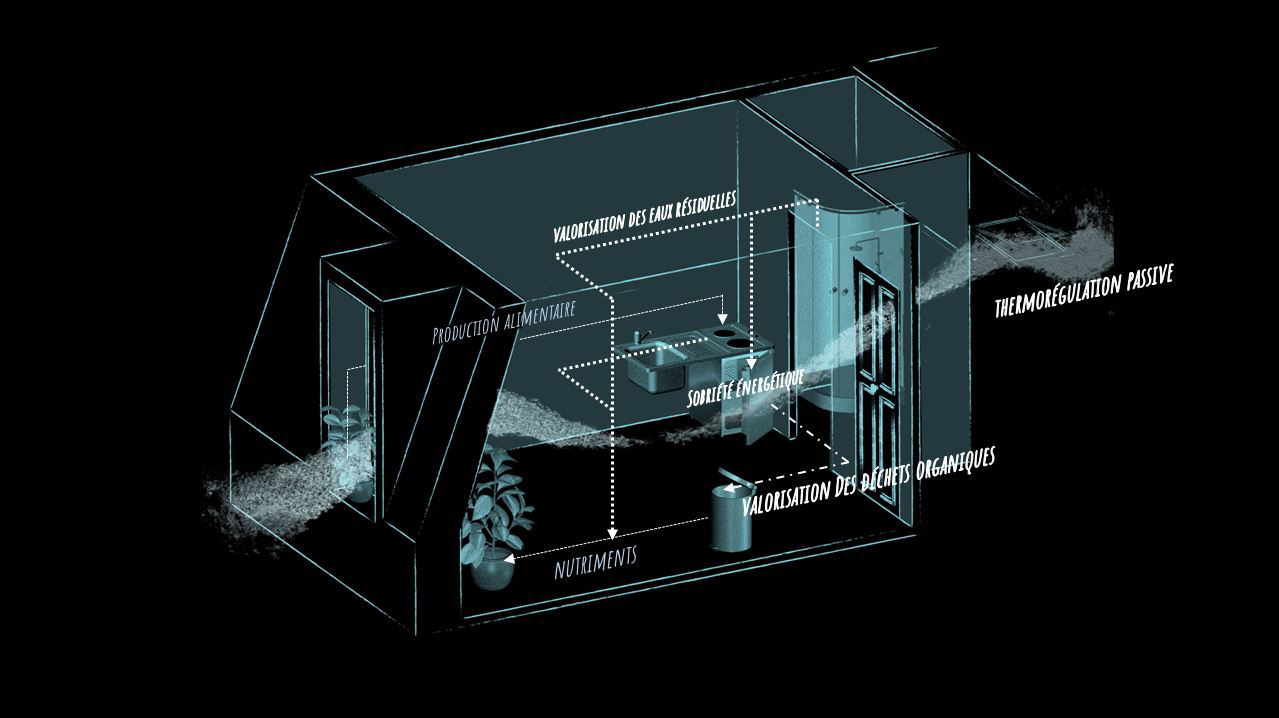

The flat as an integrated ecosystem

In order to think in a systemic way about my uses and my living environment according to my own needs, I tried to consider my flat as an ecosystem composed of objects, living beings and the flows that cross them. As a result, the solutions tested work in synergy:

To optimise daily water consumption, a tank is installed in the shower. It recovers the first few litres wasted while waiting for the water in the circuit to warm up.

In the kitchen, a small bokashi is installed to replace the waste bin and store organic waste for a few weeks, without odour or insects, until it can be deposited in specialised sorting bins for local composting and/or biogas production.

The nutrient-rich juice from the bokashi, diluted with water from the shower, is then used to feed plants placed at window level. They provide additional food (herbs, some vegetables, strawberries, etc.) but also and above all allow the flat to cool down in hot weather (dry heat) thanks to the combined evapotranspiration of the plants, soil and porous ceramic pots soaked in water (on this scale, the temperature difference varies from a few tenths of a degree to one or two degrees depending on the number of plants/ceramics and the volume of the flat).

Then, by adding a ventilation grid on the door and opening a hatch in the roof, the flat naturally ventilates itself. Draughts are created by drawing in the outside air, which is cooled by the plants. The comfort is then more about the feeling of freshness created by the air in contact with the body.

At the same time, foodstuffs are preserved as passively as possible, in particular thanks to the water recovered from the shower, which is used to create a humid and cool storage environment in summer.

The detailed case of the semi-passive refrigerator

Let’s focus on this point in particular because it allows us to understand many of the issues at stake in terms of the brakes and levers of our daily transition.

To limit our footprint, beyond eating less meat and more locally, food storage is still a place of recovery that is little questioned on an individual scale.

However, the refrigerator is one of the most energy-consuming pieces of domestic equipment, particularly in the case of a small flat in a condominium where the boiler - one of the most energy-consuming pieces of equipment if the installation is designed to heat only an individual dwelling and/or large spaces - is here shared and therefore energy-optimised. However, the urban context allows for extreme proximity to general food stores, when the use of refrigeration or electric freezing allows for the conservation of large reserves of fresh food over time, due to the lack of access to local stores (as can be the case in rural areas, for example).

Moreover, contrary to what our Western habits dictate, the low temperatures and confined environment of the refrigerator greatly deteriorate the nutritional and taste qualities of fruit and vegetables. Only meat and fish, fragile dairy products and food scraps require and support this type of preservation. In fact, it has been forgotten that fruit, vegetables and cheese are living elements that continue to ripen, improve and even grow if they are kept in the right environment.

However, as we have seen above, according to the condominium regulations, which have not changed since the 1950s, I am not allowed to install a pantry on my windowsill (which is in any case south-facing and therefore not suitable for this type of equipment). However, the already very limited space of my flat does not allow me to add a cabinet for this purpose either, even though my refrigerator would be largely underused.

After having explored many passive preservation techniques to reproduce at home, each one more impressive and practical than the other (water butter dish, desert fridge for root vegetables, water jar for leaf/flower vegetables, lacto-fermentation, oil bath, pasteurized preserves, cheese bell, etc.), I undertook to transform my small apartment fridge-freezer (91L) into a micro-fridge (about 10L, i.e. the old freezer compartment)

simply by changing the thermostat component, which allows me to use the freezer in the same way as the fridge. ), I have undertaken to transform my small flat fridge-freezer (91L) into a micro fridge (10L approximately, i.e. the old freezer compartment) simply by changing the thermostat component, which allows me to increase the reference temperature of the latter. This way, I can keep most of my fragile foodstuffs cool (between 4 and 7°C) when I need them (leftovers, cream, some cheeses, occasionally fish, for 1 to 2 people). The 10L of the old freezer compartment is more than adequate for my purposes. The remaining 81L became a passive pantry by replacing the original door with a wooden door with holes and a veil to allow good ventilation. The pantry is now divided into various shelves for jars or vegetables (potatoes, onions, squash), plus a new vegetable tray made from an unglazed ceramic planter that I water (recuperated) in summer to create a cool, humid atmosphere conducive to the preservation of root vegetables and cucurbits. (You can find here the table summarising the storage environments adapted to the fruits and vegetables).

Adapting instead of replacing

In other words, this proposal is actually an intermediate solution to allow for a gradual transformation of conservation habits and by prolonging consumption habits. Reducing refrigerated space encourages people to buy less processed products and other ready- made meals, thus reducing plastic and cardboard waste at the same time. But beyond avoiding a certain amount of unnecessary consumption caused by our eating habits, it is also a way of questioning our way of “consuming” household appliances.

Today, manufacturers and distributors of household appliances are stepping up incentives and other offers to take back old appliances, many of which are still functional, by claiming lower energy consumption. However, the manufacture, transport, distribution and even management of new equipment at the end of its life - which will often be obsolete more quickly because it contains a large number of electronic components - leads to a mode of resource consumption that is an ecological aberration since it is based on a logic of infinite production that we know is anything but sustainable.

Every production action has an impact. Encouraging consumers to only care about their direct consumption, when they use it, by making invisible the environmental and human costs that are hidden behind the purchase of new equipment, is a very problematic commercial strategy. Moreover, one of the criticisms that can be made here of the eco- design of such objects, however virtuous their means of production and however economical their use, is that the energy consumption linked to an object necessarily depends on the user’s willingness to use it sparingly. An eco-designed household appliance will therefore not necessarily mean financial or energy savings in use. Moreover, throwing away an appliance that is still perfectly functional would have been counterproductive, and selling it would only have shifted the responsibility for its consumption to someone else.

It is in view of these limitations that I decided to adapt my existing fridge rather than replace it. Firstly, keeping the interior of my old fridge allows me to optimise the space and the existing material to fulfil this function, without risking compatibility problems and redundancy of uses (problems raised in the Ergonomics and low tech report).

On the other hand, doing without a refrigerated storage environment meant taking the risk of wasting food leftovers or poisoning myself, and dedicating time every day to cooking for each meal, which generally does not correspond to my personal rhythm of life (I cook for two to three meals). Finally, keeping my old fridge but making internal transformations to change its use allows me to keep a certain social and technical accessibility to the use (innovation easily appropriated because sufficiently close to a known reference).

Moreover, giving a second life to this object by changing its use and its aesthetics, rather than starting from scratch by buying another piece of equipment, helps to create a new relationship with objects. In the case of this refrigerator, the example is all the more significant as it touches on the register of technological equipment, the most obsolescent objects in our current culture.

Adapting rather than replacing, voluntarily modifying one’s uses and reappropriating techniques that are sources of autonomy rather than changing for equipment that is a priori less consuming in use, this is what the modest transformation of this refrigerator is trying to defend. It is a transitional stage to make it pass from the status of an indispensable object, out of habit, to that of an auxiliary object, useful in case of necessity. Let us underline in passing that it is also possible to replace the door by a curtain, or any other technique more easily achievable at home and at a lower cost for those who would not have the desire, the means, the skills or the possibility to go near a wood workshop.

However, modifying one’s equipment is not enough on its own and must be accompanied by sensible consumption practices, for example by buying food in reasonable quantities. With this system, it is possible to buy the equivalent of one or two weeks’ worth of fresh produce, but only if you take care to consume the most fragile products first to avoid food waste. For example (and the difficulty will be the same with a conventional fridge), fresh spinach or salads should be consumed within a few days of purchase or they will wilt.

To conclude on this point, in nearly six months of use, this operation has revealed, for my part, several notable improvements and benefits.

On the one hand, the vegetables keep much better and longer than in my old fridge, and even grow back to be able to feed me two or three times, as in the case of the leek kept with its feet in water. Moreover, I have noticed a certain comfort of use and a personal fulfilment in the satisfaction of controlling my food, from preservation to cooking. On the other hand, a certain improvement of my personal energy balance is to be declared, with a consumption reduced by a third every day (less long and less frequent compression time, therefore less electricity consumption since a refrigerator is only under tension when it compresses the refrigerant gas to lower the temperature in the cabin).

Living differently in a flat, one year later

One year after the start of the project, at first sight, the difference in my electricity bills is not obvious. But this can be explained by a double change in my habits. On the one hand, I have reduced and optimised my current use of electrical objects, and on the other hand, I have increased my teleworking from home since I started working for myself. However, the latter consumption, mainly linked to digital technology, is not, in absolute terms, additional consumption linked to my change of lifestyle, but rather a shift in my daily consumption towards my home, which has also become my main place of work.

As a result, if I had not made these initial changes to revise my uses, my electricity bills would have shown an overall increase rather than a constant curve. Ultimately, my digital consumption will be the next point I would like to look at in order to find potential adaptations.

As far as my water consumption is concerned, I have noticed an approximate reduction of 20% compared to my past habits (the flat does not have an individual meter, this percentage comes from the “manual” calculation of my average weekly uses). But beyond the significant savings, the greatest contribution of this project is the potential for empowerment that these devices allow. By questioning myself on my uses and the functioning of the equipment I depend on on a daily basis, I have, for example, reappropriated some electrical know-how which has made me more autonomous in repairing or transforming my equipment. More generally, this project has enabled me to become a real player in the management of my home: monitoring of consumption, control of water supplies and the electrical panel in case of problems, thermal regulation of my hot water tank according to the season and my needs, etc. Philosophically, my flat is no longer simply a place of storage and subsistence. These simple transformations of the habitat have completely transformed my way of inhabiting space. It has become an interconnected ecosystem in which the flows of water, air, matter and energy work in synergy. It is self-sustaining through the coordinated action of humans, micro-organisms and plant that benefit each other.

5.MAKE PROJECT - LEVERAGE #

In conclusion, all the systems discussed above are intended to designate possible places of recovery and diversion, among an infinite number of others that remain to be explored. They are designed to be easily and cheaply realised, alone or with support, at home or with the help of shared workshops/fablabs and other neighbourhood resource centres.

What really counts here is the process of reappropriating know-how and ways of living in society, beyond the object or technique itself.

Beyond our determination to carry the voice of the inhabitants by sitting in general assemblies alongside the co-owners, in order to co-construct larger renovation projects over time, our collective is growing little by little, and it is ultimately a rehabilitation of our way of living together in these spaces that is at work here.

In the long term, the challenge is that this experience can inspire, from one person to the next, other people who will in turn be able to reappropriate this approach. It can be summed up quite simply in a few key words: QUESTION and DIAGNOSE the context, needs and uses SEARCH for pre-existing solutions to respond to the problems raised EXPERIMENT using these solutions as inspiration REAPPROPRIATE them on a daily basis, according to one’s personal context, then SHARE them with others, to enrich the experimentation through collective intelligence.

It is then that the global project will become truly political, because it tends to spread throughout the citizenry a capacity to question the established codes, acquired habits and social conformism that slow us down in our desire to make transitions. This shift from the individual to the political would potentially be the starting point of a cultural shift which is, in my opinion, the greatest lever for transition that we have at the moment.

Finally, reclaiming one’s habitat is a political act. It means understanding, integrating and taking care of the ecosystem in which we are part and on which we depend.

It is about rebuilding society!

Acknowledgements

To conclude this article, I would like to thank the Low-tech Lab. In particular, I would like to thank Quentin Mateus, who followed the reflection and conception of this project, and Solène de Jacquelot for offering me this space to speak and to transmit my work.

I would also like to thank the person who shares my daily life and who has activelyfollowed my experiments, but also and above all all the inhabitants and owners of the building who have invested in or supported such a project. It is thanks to them that the project has come to fruition.